"Regular meditators enjoy better and more fulfilling relationships." - Professor Mark Williams, Mindfulness: A practical guide to peace in a frantic world (2011), p6.

"If you are not in touch with yourself, it is very unlikely that your connections with others will be satisfactory in the long run. The more centered you are yourself, the easier it will be for you to be centered in your relationships, to appreciate connectedness with others, and to be able to fine-tune it. This is a very fruitful area of application of the meditation practice..." - Mindfulness MBSR Founder Dr. Jon Kabat-Zinn, Full Catastrophe Living (2005), p222-223.

"...as we endeavor to practice with relationships, we begin to see that they are our best way to grow. In them we can see what our mind, our body, our senses, and our thoughts really are. Why are relationships such excellent practice? Why do they help us to go into what we might call the slow death of the ego? Because, aside from our formal sitting, there is no way that is superior to relationships in helping us see where we’re stuck and what we’re holding on to. As long as our buttons are pushed, we have a great chance to learn and grow. So a relationship is a great gift, not because it makes us happy—it often doesn’t—but because any intimate relationship, if we view it as practice, is the clearest mirror we can find." - American

Zen teacher Charlotte Joko

Beck, Everyday

Zen (1997), p88-89.

"I was talking to a student about my relationship with my wife. I often complain, but I don’t think I can live without her. That is, to tell the truth, what I really feel." - Japanese Soto Zen teacher Shunryu Syzuki, Branching

Streams Flow in the Darkness (1999), p179.

"Living together is an art. Even with a lot of goodwill, we can still

make the other person very unhappy. Mindfulness is the paintbrush in the

art of happiness. When we are mindful, we are more artful and happiness

blooms." - Vietnamese

Zen teacher Thich Nhat

Hanh, Fidelity: How to Create a Loving Relationship That Lasts (2011), p102.

"Never cling to what is dear and what is not dear.

Not seeing what is dear and seeing what is not dear, are both painful.

Hence hold nothing dear, for separation from what is dear is bad.

There are no bonds for those to whom nothing is dear or not dear.

[...].

Whoever has virtue and insight, and cultivates with Dharma realizes the Truths and fulfils his own duties — all people hold dear to him." - The Buddha, Dharmapada Sutra (Narada Translation, 1959), Chapter 16: Affection, Pleasing, Sorrow, Attachments (209-217)

"The bodhisattva* Nāgārjuna once said the following: [...] “Both lay people and monastics can reach the Other Shore, but even so, each way has its difficult and its easy aspects. Those in lay life have all manner of duties and occupations. If they should wish to concentrate on pursuing wholeheartedly the Path to full awakening, then their family duties will fall by the wayside, and if they should wholeheartedly fulfill the responsibilities of family life, then matters that pertain to pursuit of the Way will be abandoned. They would need to be able to practice the Dharma without selecting one way and abandoning the other. And this is what I would describe as ‘taking on what is difficult’. In leaving lay life behind, we sever ourselves from pursuing worldly profits and from indulging in dislikes and wrangling, as we devote ourselves wholeheartedly to practicing the Way, which is what I would describe as ‘taking on what is easy’. Also, there is the noise and bustle of a home, with its many affairs and many duties, all of which are the roots of entanglements and the storehouse of wrongdoings. This is what is described as ‘taking on what is extremely difficult’." - Japanese

'Soto Zen' Founder Master Eihei

Dogen, Shobogenzo (Translated

by Hubert Nearman, 2007), p904-905.

Vietnamese

Zen teacher

Thich Nhat

Hanh, in his book

Fidelity: How to Create a Loving Relationship That Lasts (2011), writes the following of the situation facing those who enter long-term relationships in the West, p94:

"The U.S. divorce

rate is around fifty percent, and for nonmarried but committed partners,

the rates are similar or higher"

Directly before this he states:

"When we commit to a partner, either in a marriage ceremony or in a

private way, usually it is because we believe we can be and want to be

faithful to our partner for the whole of our lives. That is a

challenge that requires consistent strong practice. Many of us don’t

have any models of loyalty and faithfulness around us."

This leaves at least half of couples in a hopeless situation - very likely triggering cold, business-like approaches to marriage and raising a family. As American

Zen teacher

Charlotte Joko

Beck states in her book

Everyday

Zen (1997), p96:

"...all weak relationships reflect the fact that somebody wants something for himself or herself."

Although such selfish intentions can remain hidden for periods of time - bleached by the bright rays of sensual love, such relationships cannot function effectively for very long. As Joko Beck describes from personal experience, p72:

"As the months go by the dream collapses under pressure, and we find that we can’t maintain our pretty pictures of ourselves or of our partners. Of course we’d like to keep the ideal picture we have of ourselves. I’d like to believe that I’m a fine mother: patient, understanding, wise. (If only my children would agree with me, it would be nice!) But still, this nonsense of emotion-thought dominates our lives. Particularly in romantic love, emotion-thought gets really out of hand. I expect of my partner that he should fulfill my idealized picture of myself. And when he ceases to do that (as he will before long) then I say, “The honeymoon’s over. What’s wrong with him? He’s doing all the things I can’t stand.” And I wonder why I am so miserable. My partner no longer suits me, he doesn’t reflect my dream picture of myself, he doesn’t promote my comfort and pleasure. None of that emotional demand has anything to do with love. As the pictures break down — and they always will in a close relationship — such “love” turns into hostility and arguments."

Thich Nhat Hanh writes in

Fidelity (2011) that from such difficulty the seeds of separation and divorce sprout, only for us to begin to repeat the same process again with a new partner, p29:

"It’s common practice, when we encounter difficulty and suffering with

our partner or spouse, to think we need to separate or divorce. By

getting away from the other person, we think we’ll have freedom. We

think that person is the cause of our suffering. But the truth is that

even though we may feel freer right after the divorce or separation, we

often get entangled immediately with someone else. We may stick to this

new person, but we end up acting just like we did with the last one. We

are the victims of our own habits. The way we think, speak, and act has

not changed. What we did to cause suffering to the first person, we now

do to cause suffering to someone new, and we create a second hell."

And all of this is our own making, p51:

"It’s not other people who confine us; we confine ourselves. If we feel

trapped, it’s due to our own actions. No one is forcing us to tie

ourselves up. We take the net of love and we wrap ourselves in it."

So ultimately we only have ourselves - our habitual appetites and behaviours - to blame for our self-confinement, as mindfulness teacher

Dr. Jon Kabat-Zinn also states in

"Practice anger and isolation in a relationship for forty years, and you wind up imprisoned in anger and isolation. No big surprise.[...] Ultimately, it is our mindlessness that imprisons us. We get better and better at being out of touch with the full range of our possibilities, and more and more stuck in our cultivated-over-a-lifetime habits of not-seeing, but only reacting and blaming."

Some couples think that having a baby together will somehow dissolve their isolation from one another, but as Thich Nhat Hanh writes in

Fidelity, it does not work, p37:

"Even if two people have a baby together, they are still separate. Each

of us remains in isolation. It’s not by living together, or by having

sexual relations, or even by having children together that we can dispel

this feeling of isolation."

This feeling of isolation, having been present before one meets one's partner, is not clear at the beginning of a relationship, however - there is a 'honeymoon period' filled with lots of joy and excitement revolving around indulgence in sensual love, p93:

"In the beginning of a relationship, you’re very passionate."

This is until that state has clouded one's perception to the point that suffocating attachment has inevitably crept in and tipped the balance towards aversion, p12:

"Love can be our greatest joy or — when it gets confused with craving and attachment — our greatest suffering"

This is not something most people are unfamiliar with, of course. As Thich Nhat Hanh, a celibate monk, says in

Fidelity, p45:

"Most of us have tasted the suffering of sexual craving."

And he acknowledges the biological roots of this craving, p17:

"Every living thing wants to continue into the future. This is true of

humans, as well as of all other animals. Sex and sexual reproduction are

part of life."

In addition to coming together romantically for sexual reproduction or for nurturing of life in general, however, there is also another dimension I heard Thich Nhat Hanh talk about in 2010 when I stayed at Plum Village - that of satisfying a need to recreate the intimacy and affection one enjoyed as an infant. This movement from seamless integration with a larger whole, to one of separation and maturation - from the womb to the outside world - creates a longing for a return to a similar comfortable, protected, provided-for wholeness via a human intermediary. It could possibly be the origin of every spiritual path - seeking Oneness with the universe, Union with a Creator, or True Love. Thich Nhat Hanh writes of this situation in

Fidelty, p22:

"As newborns, we could distinguish the smell of our mother or the person taking care of us. We

knew the sound of her voice. We came to love that smell and that sound.

That’s the first, original love, born from our need; it’s completely

natural. When we grow up and look for a partner, the original desire

to survive is still there in many of us. We think that without someone

else, we can’t survive. We might be looking for a partner, but the child

in us is looking for that feeling of safety and comfort we had when our

parent or caregiver arrived."

One may hear romantic partners speak to each

other in a 'baby voice', or call each other "baby" or "babe" - an apparent reinforcing of the child-like neediness that can manifest in a romantic relationship. What can start out as a mutual agreement to love one another unconditionally can very easily become distorted into a situation where two people are attempting to manipulate one another into fulfilling their own selfish needs - attempting to satisfy juvenile appetites left over from when they were vulnerable children. This immature 'thumb-sucking' - seeking to satisfy a sensual craving rooted in a left-over need for existential security from a parent-figure, coupled with the psychological gratification associated with the reproductive impulse, and the pleasures which accompany sexual gratification, can create a situation tainted with suffocating possessiveness, rather than liberating empowerment, and thus deep suffering, as Thich Nhat Hanh says in Fidelity, p21:

"Every human being wants to love and be loved. This is very natural. But

often love, desire, need, and fear get wrapped up all together. There

are so many songs with the words, “I love you; I need you.” Such lyrics

imply that loving and craving are the same thing, and that the other

person is just there to fulfill our needs. We might feel we can’t

survive without the other person. When we say, “Darling, I can’t live

without you. I need you,” we think we’re speaking the language of love.

We even feel it’s a compliment to the other person. But that need is

actually a continuation of the original fear and desire that have been

with us since we were small children."

And suddenly one can find oneself 'netted' like a fish raised out of the nourishing water; gasping for our lives - we experience this as 'lovesickness'; a current which washes over everything we perceive, p86:

"In sensual love, volition can look like a kind of sickness called

“lovesickness.” We are addicted to the shadow of a figure, and we cannot

forget him or her. When we are caught in the net of sensual desire, all

our longings and our perceptions are dyed the color of sensual love.

When walking we think about it; when sitting we think about it. Watching

the moon we also remember it; watching a cloud we remember it again.

The mind of sensual desire is a current; it’s not a block or a clod of

earth. The current sweeps our thoughts, perceptions, and everyday

actions along with it."

This is not to say that nothing positive remains; of course there are noble intentions somewhere in the mix, and yet as Joko Beck states in

Everyday Zen, we need to identify which parts are genuine and which parts are merely emotionally-driven, p72:

"In that relationship there’s always some genuine love and some false love. How much of our love is genuine depends on how we practice with false love, which breeds in the emotion-thought of expectations, hopes, and conditioning. When emotion-thought is not seen as empty, we expect that our relationship should make us feel good. As long as the relationship feeds our pictures of how things are supposed to be, we think it’s a great relationship."

Thich Nhat Hanh goes into more detail on how our internal images of how our relationships should be - often based on selfish needs - bring about unnecessary suffering, in his book

Understanding Our Mind (2001), p58:

"When we fall in love, for example, we usually fall in love with an

image we have of our beloved. We cannot eat, sleep, or do anything

because this image in us is so strong. Our beloved is beautiful to us,

but our image of him may actually be far from the reality. We don’t

realize that the object of our perception is not the reality-in-itself

but an image we have created. After we marry and live with our beloved

for two or three years, we realize that the image that we held on to and

stayed awake at night thinking about was largely false. The object of

our perception, our image of our beloved, belongs to the second mode of

perception, the mode of representations. Our consciousness manifests an

image of the object and we love that image. The image we love may have

nothing to do with the person-in-himself. It is like taking a photograph

of a photograph."

The addiction to this image happens very subtly as the various sensual desires it gratifies; the mind seeking procreation, the tactile nervous system, the desire to be 'mothered', all intermingle and create a seemingly tangible and perfect sensual whole that becomes one's master. Thich Nhat calls this big, seemingly perfect tangle of powerful sensual addiction an "internal knot", in

Understanding Our Mind, p363:

"Addiction is an internal knot. We do not start out being addicted to drugs, alcohol, or an unwholesome relationship. The knot is tied gradually. If internal knots announced themselves with a loud noise when they formed, we would know immediately that they were there. But we can’t discern the moment when we became addicted to drugs or alcohol. We don’t know exactly when we became infatuated with someone who is not good for us. The process of the formation of an internal knot happens stealthily."

And the image created by the knot we hold onto controls us in powerful ways, as he writes in

Fidelity, p18:

"When we’re trapped by sensual love, we spend our time worrying that the other person will leave or betray us."

As time goes on, however, the power of that image diminishes somewhat, p93:

"The first year of a committed relationship already reveals how difficult

it is. When you first commit to someone, you have a beautiful image of

them, and you commit to that image rather than the person. When you live

with the person twenty-four hours a day, you begin to discover the

reality of the other person doesn’t quite correspond with the image you

have of him or her."

As one wrestles with one's 'post-honeymoon' situation - the reality which was hiding behind the bright rays of sensual love all along - one finds that one's partner can very quickly become like a private stranger, and one feels no shame in looking elsewhere. Thich Nhat Hanh has the following to say on this in Fidelity, p93:

"...passion may only last a short time—maybe six months, a year, or two

years. Then, if you’re not skillful, if you don’t practice mindfulness,

concentration, and insight, suffering will be born in you and in the

other person. When you see someone else, you might think you’d be

happier with them. In Vietnam, there is a saying: “Standing on top of

one mountain and gazing at the top of another, you think you’d rather be

standing on the other mountain.”"

Having made important promises and declared deep romantic feelings, however, can mean one's social integrity and reputation can be heavily undermined if one is to break away from the commitments one has made to a family. When under such pressures, Thich Nhat Hanh says that we can survive in relationships grounded in love; that our commitments can be honored if we send down deep, healthy roots to weather the inevitable storms, p95:

"To keep our commitment to our partner and to weather the most difficult storms, we need strong roots."

And the strength of such roots depends on how well we can transform, or uproot, our unhealthy habits, p29:

"If we aren’t yet able to transform... habit energy, we will come out

of the prison of one relationship only to fall into the prison of

another."

Our unhealthy habits are rooted in our unaccepted internal pain and emotional reactiveness - our sympathetic nervous system or adrenaline response which causes us to fight/freeze/flee when faced with certain responsibilities. Therefore it is within this internal landscape unifying mind and body where the work of dealing with habits in the context of one's relationship begins. Mindfulness teaches one to approach oneself first with the kind of love and care one wishes to direct towards one's partner, p77:

"...self-love is crucial for loving another

person. A successful relationship depends on us recognizing our own

painful feelings and emotions inside — not fighting them, but accepting,

embracing, and transforming them to get relief."

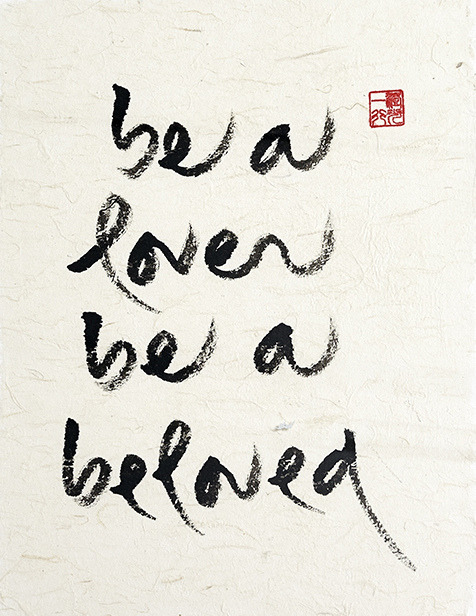

This compassionate, all-accepting 'true love', if harnessed effectively, heals oneself as an individual as well as one's relationship simultaneously. Here is

Fidelity on this phenomenon, p81:

"In true love, there

is no distinction between the one who loves and the one who is loved.

Your suffering is my own suffering. My happiness is your happiness.

Lover and beloved are one. There’s no longer any barrier. True love has

this element of the abolishing of self. Happiness is no longer an

individual matter. Suffering is also no longer an individual matter.

There’s no distinction between us. In true love, you don’t exclude

anyone. If your love is true love, it will benefit not only humans, but

also animals, plants, and minerals. When you love one person, it’s

an opportunity for you to love everyone, all beings. Then you are going

in a good direction, and that is true love. But if you love someone and

you get caught up in suffering and attachment, then you get cut off from

others. That’s not true love."

If only one partner walks this path, however, the difficulties of living within a relationship will not apparently ever be overcome. Dedication to the path of true love is necessary for both partners, as Thich Nhat Hanh states, p19:

"Once you have a spiritual path, you have a home. Once you can deal with

your emotions and handle the difficulties of your daily life, then you

have something to offer to another person. The other person has to

do the same thing. Both people have to heal on their own so they feel at

ease in themselves; then they can become a home for each other.

Otherwise, all that we share in physical intimacy is our loneliness and

suffering."

This approach makes romantic partners into more than mere lovers; they become spiritual partners of sorts, p95:

"A true spiritual partner is one who encourages you to look deep inside yourself for the beauty and love you’ve been seeking."

Since such spiritual discipline and dedication often requires favourable environmental and interpersonal conditions, some romantic relationships inevitably finish prematurely, as Joko Beck writes in

Everyday Zen, p100:

"All relationships can teach us something;

and some of them, sadly, must come to an end. There may come a time when

the best way to serve the true self is to move on."

Until such a catastrophe occurs, however, partners can work on healing their dying relationship by approaching themselves and each other in a more skilful, realistic, and selfless way. Joko Beck suggests aiming for a practical, functional, resilient, yet open quality inspired by the necessary conditions all life needs to flourish - flexible yet strong, like a bamboo stem or cell membrane, or, as she describes, a structure which can withstand storms, in

Everyday Zen, p97:

"I’ve

heard about a way of designing houses at the beach, where big storms

can flood houses: when they are flooded, the middle of the house

collapses and the water, instead of taking down the whole house, just

rushes through the middle and leaves the house standing. A good

relationship is something like that. It has a flexible structure and a

way of absorbing shocks and stresses so that it can keep its integrity,

and continue to function. But when a relationship is mostly “I want,”

the structure will be rigid. When it is rigid, it can’t take pressure

from life and so it can’t serve life very well. Life likes people to be

flexible so it can use them for what it seeks to accomplish."

Part of such an accommodating, flexible structure to a relationship is the practice of communicating mindfully - with an awareness of when emotion is colouring proceedings, and knowing when to skilfully withdraw when anger or unhealthy appetites are dominating expression, rather than grounded, heart-felt reflection. Dr. Jon Kabat-Zinn speaks of this in his book

Full Catastrophe Living (2005) as follows, p375:

"Relationships

can heal just like bodies and minds can heal. Fundamentally, this is

done through love, kindness and acceptance. But in order to promote

healing in relationships or to develop the effective communication such

healing depends on, you will have to cultivate an awareness of the

energy of relationships, including the domains of minds and bodies,

thoughts, feelings, speech, likes and dislikes, motives and goals -- not

only other people's but also your own - as they unfold from moment to

moment in the present. If you hope to heal or resolve the stress

associated with your interactions with other people, whoever they may

be... mindfulness of communication becomes of paramount importance."

Once an intention to be mindfully communicative and resilient has been shouldered by both partners within a relationship, then it seems the real daily practice can begin - of dissolving emotional reactiveness to the inevitable pain accompanying toxic sensual craving, with the benefit of mutual encouragement. This must necessarily begin with oneself, as Thich Nhat Hanh states in

Fidelity, p51:

"If

you don’t know how to handle a painful feeling in you, how can you help

another person to do so?"

As one becomes more competent at accepting one's own pain, one simultaneously heals one's partner, as Joko Beck writes in her book

Nothing

Special - Living Zen (1995), p269:

"When I heal my pain, without any

thought at all I heal yours, too. Practice is about discovering that my

pain is our pain."

This mindfulness practice is, Thich Nhat Hanh says, in

Understanding Our Mind, the greatest gift a partner can ever offer, p345:

"The greatest gift that we can offer to our beloved is our true

presence. Practice walking meditation, sitting meditation, and breathing

mindfully to be present for your beloved. When she suffers, practice

conscious breathing and say to her, “Darling, I know that you suffer.

That is why I am here for you.” If you suffer, you have to practice

breathing in and out and say, “Darling, I suffer. Please help.” When you

love someone, there must also be trust. If you suffer, you should be

able to go to those you love and tell them that you suffer and need

their help. In true love, there is no room for pride or arrogance. Go to

him and tell him that you suffer and need his help. If you cannot,

something is wrong in your relationship. It is important to practice

this. Without true presence, how can you love and care for one another?

You generate the energy of mindfulness in order to be truly present. The

most beautiful declaration of love is, “Darling, I am here for you.”

When you pronounce this mantra, there will be a transformation in both

of you. This is the practice of mindfulness."

And this gift needs to be given with a sentiment of nothing less than pure charity - pure selflessness, in order to have the greatest impact upon both partners' lives, as Joko Beck explains in

Everyday Zen, p93-94:

"The

only thing that works (if we really practice) is a desire not to have

something for myself but to support all life, including individual

relationships. Now you may say, “Well, that sounds nice, I’ll do that!”

But nobody really wants to do that. We don’t want to support others. To

truly support somebody means that you give them everything and expect

nothing. You might give them your time, your work, your money, anything.

“If you need it, I’ll give it to you.” Love expects nothing. Instead of

that we have these games: “I am going to communicate so our

relationship will be better,” which really means, “I’m going to

communicate so you’ll see what I want.” The underlying expectation we

bring to those games insures that relationships won’t work. If we

really see that, then a few of us will begin to understand the next

step, of seeing another way of being. We may get a glimpse of it now and then: “Yes, I can do this for you, I can support your life and I expect nothing. Nothing.”"

This does not mean that one mindlessly gives oneself away to one's relationship - instead one sees one's practice within one's relationship in the context of a broader, shared 'true self' that permeates all humanity, and even within Nature and the universe; within the Dao. Joko has the following to say on this in

Everyday Zen, with particular emphasis on serving a Master of sorts beyond the realm of sensual love and human procreation, p99:

"In any situation our devotion

should be not to the other person per se, but to the true self. Of

course the other person embodies the true self, yet there is a

distinction. If we are involved in a group, our relationship is

not to the group, but to the true self of the group. By the “true self”

I’m not talking about some mystical ghost that floats above. True self

is nothing at all; and yet it’s the only thing that should

dominate our life; it is the only Master. Doing zazen [formal seated mindfulness meditation], or sitting

sesshin [mindfulness meditation reatreat], is for the purpose of better understanding our true self. If we

don’t understand it, then we will be confused forever by problems and

won’t know what to do. The only thing to be served is not a teacher, not

a center, not a job, not a mate, not a child, but our true self."

This "true self", or Dao; 'what is', can be engaged with at any moment, in order to take the most effective course of action, and that course of action is spontaneous, non-verbal; beyond philosophical reflection on love and life - all the while delivering more joy. Here is Joko Beck again in

Everyday Zen, p100:

"No one can tell me

what is best; no one knows except my true self. It doesn’t matter what

my mother says about it, or what my aunt says about it; in a certain

sense it doesn’t even matter what I say about it. As one teacher says,

“Your life is none of your business.” But our practice is definitely our

business. And that practice is to learn what it means to serve that

which we cannot see, touch, taste or smell. Essentially the true self is

no-thing, and yet it is our Master. And when I say it’s no-thing, I

don’t mean nothing in the ordinary sense; the Master is not a thing, yet

it’s the only thing. When we’re married, we’re not married to each

other, but to the true self."

In this way mindfulness practice demands recognition of 'what is' - what is really happening within a relationship - within our seamless minds and bodies, and for us to practice embracing any difficulty, as Thich Nhat Hanh writes in

The Heart of Buddha's Teaching (1999), p37:

"If we are in a

difficult relationship, we recognize, "This is a difficult

relationship." Our practice is to be with our suffering and take good

care of it."

It is necessary to do this over and over again - continually, since, as Joko Beck states in

Everyday Zen, no relationship will ever be perfect, even if both partners are practicing mindfulness for their whole lives together, p72-73:

"...if we’re

in a close relationship, from time to time we’re going to be in pain,

because no relationship will ever suit us completely. There’s no one we

will ever live with who will please us in all the ways we want to be

pleased. So how can we deal with this disappointment? Always we must

practice getting closer and closer to experiencing our pain, our

disappointment, our shattered hopes, our broken pictures. And that

experiencing is ultimately nonverbal. We must observe the thought

content until it is neutral enough that we can enter the direct and

nonverbal experience of the disappointment and suffering. When we

experience the suffering directly, the melting of the false emotion can

begin, and true compassion can emerge."

As couples grow in this way together, their understanding of one another also grows - they become truly known to one another - and so become closer and closer as they simultaneously grow closer to their own individual (and yet shared) 'true selves', thus dispelling the loneliness which undermines long-term commitment. Thich Nhat Hanh writes in

Fidelity, p37:

"We

can transform this feeling of loneliness only when we truly understand

ourselves and our loved ones.[...] We can only dispel our mutual

isolation when we practice mindfulness and

are able to truly come home to ourselves and each other."

This constant awareness of one's inner landscape means the tension associated with unhealthy attachment is dissolved before it can harden into a knot which blinds one - something Thich Nhat Hanh refers to in

Understanding Our Mind, p363:

"If we are guarding the six senses, ...as soon as we have a feeling of attachment, we will be aware of it. We know that we have a sweet feeling of attachment when we hold a glass of wine or a cigarette, or toward a person we should not be so close to. We know where this pleasant feeling is going to take us. With mindfulness — the recognition of what is happening as it is happening — the internal knot of attachment will not be able to form without our noticing it until it is too late."

By not tangling ourselves into knots, a restrictive net is not woven around and within us, and we love others in a more liberating way, as stated in

Fidelity, p10:

"Love can bring us happiness and peace as long as we love in such a

way that we don’t make a net to confine ourselves and others. We can

tell the correct way to love because, when we love correctly, we don’t

create more suffering."

This compassionate, healing love even expands out from one's relationship to all sentient beings in one's environment, p81:

"Cultivating the four elements of true love — loving kindness, compassion,

joy, and equanimity — is the secret to nourishing deep and healthy

relationships. When you practice with these elements regularly, you can

handle the difficulties in your relationships and transform the

suffering you feel inside.You become like a Buddha. You love everyone

and every species. Your presence in the world becomes very important,

because your presence is the presence of love."

In this sense, a romantic couple practicing loving one another mindfully exist as a facet of life in harmony with life itself - as a larger organism constructed from smaller symbiotic organisms existing beyond the needs and wants of the individuals involved. Joko Beck points this out in

Everyday Zen, p95-96:

"...life gets in working with it as a channel. A good relationship gives

life more power. If two people are strong together, then life has a

more powerful channel than it has with two single people. It’s almost as

though a third and larger channel has been formed. That is what life is

looking for. It doesn’t care about whether you are “happy” in your

relationship. What it is looking for is a channel, and it wants that

channel to be powerful. If it’s not powerful life would just as soon

discard it. Life doesn’t care about your relationship. It is looking for

channels for its power so it can function maximally. That functioning

is what you are all about; all this drama about you and him or her is of

no interest to life. Life is looking for a channel and, like a strong

wind, it will beat on a relationship to test it. If the relationship

can’t take the testing, then either the relationship needs to grow in

strength so that it can take it, or it may need to dissolve so something

new and fresh can emerge from the ruins. Whether it crashes or not is

less important than what is learned."

And when such a couple exist within a mindful community containing other mindful couples, then they may harness mindfulness in it's strongest manifestation, as Thich Nhat Hanh states in

Fidelity, p99:

"When the three roots of faith, practice, and community support have fed

us deeply, then we will be solid both alone and in our relationships. We

will not just survive; we will flourish. No violent storm can throw us."

For the modern world this is not easy to find, if at all, and yet even just two people - whether in a relationship or not - can form a community (a Sangha) stable enough to mutually support rewarding mindfulness practices, p45:

"Even if you are just two people, if you nourish each other’s joy and

mindfulness, then you have a Sangha, a mindful community. If your family

only has two people, that is the smallest Sangha. If you have a child,

you have three Sangha members."

With dedicated and focused practice, something truly tangible and rewarding can be achieved. Joko Beck writes in

Everyday Zen, p73:

"The more we practice over the years, the more an open and loving mind develops. When that development is complete (which means that there is nothing on the face of the earth that we judge), that is the enlightened and compassionate state. The price we must pay for it is lifelong practice with our attachment to emotion-thought, the barrier to love and compassion."