"It is believed that, since calligraphy is a highly individualized art, writing offers a glimpse of the heart." - Wendan Li, Chinese Writing & Calligraphy (University of Hawai‘i Press. 2009), p181

"If our heart is light and open, unfettered by internal formations, the world is beautiful. True mind conditions the world of suchness and happiness, because it is not caught in attachment." - Vietnamese Zen teacher Thich Nhat Hanh, Understanding Our Mind (2001), p40.

"In Eastern language, the word for mind and heart is often the same word,

which is heartfulness. ... Heartfulness is giving attention to anything

that you can perceive with a sense of warmth" - Shamash Alidina, Mindfulness for Dummies (2010), p60.

In my previous post,

The Dao of Chinese Insight Calligraphy, I mentioned that the Chinese considered

heart and mind to be one thing -

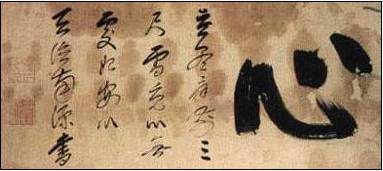

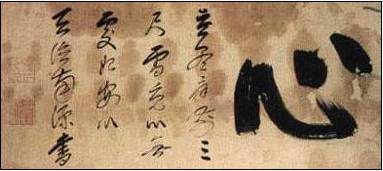

Xīn (

心).

|

| A 17th Century Japanese Zen Calligraphy piece - the large character is the word for heart/mind; Xīn (心). |

There is an ancient Chinese 4 character idiom (

Chengyu 成语) about the manifestation of the human heart inspired by the Daoist Classic

JuangZi, which goes as follows:

"得心应手" (dé xīn yìng shǒu) - "From heart to hand"

My Insight Calligraphy teacher here in Beijing,

Paul Wang, told me today that this idiom comes from

JuangZi,

Chapter 13: The Way of Heaven, where a Duke demands a demonstration of a wood-worker's wisdom. The wood-worker says:

"When I chisel a wheel, if the blows of the mallet are too gentle, the chisel slides and won't take hold. But if they're too hard, it bites in and won't budge. Not too gentle, not too hard - you can get it in your hand and feel it in your mind. You can't put it into words, and yet there's a knack to it somehow."

|

| The inscription on this Chinese calligraphy brush reads: "From heart to hand" - a Chinese idiom inspired by the Daoist Classic text JuangZi. |

Paul said that the idiom is used to describe the state of understanding one thing very well in the sense that one can manifest it's essence very skillfully. This emphasis on skill allowing the positive contents of a person's heart to be expressed appears to have an intimate relationship with mindfulness practice. Vietnamese Zen teacher Thich Nhat Hanh includes in his book,

The Miracle of Mindfulness (1987), in the Sutra Section: The Foundation of Mindfulness (

Satipatthana Sutta), how the Buddha compared the skill of a wood-turner to a monk being mindful of his breath, p112-113:

"Just as a skillful turner or turner's apprentice, making a long turn, knows "I am making a long turn," or making a short turn, knows, "I am making a short turn," just so the monk, breathing in a long breath, knows "I am breathing in a long breath"; breathing out a long breath, knows "I am breathing out a long breath"

The art of Chinese calligraphy writing has a long-standing relationship with this idea of honing deep skills - creative skills which have the potential to spontaneously render the heart in a true and highly expressive way. As Wendan Li, author of

Chinese Writing & Calligraphy, writes, p17:

"the complex internal structure of Chinese characters and the unique writing instruments have allowed ample space in multiple dimensions for Chinese calligraphy to develop into a fine art whose core is deeply personal, heartfelt expression."

A little later, Li states what seems to be the ideal of the calligrapher accomplishing his task, p27:

"the artist pours out heart and soul onto a piece of paper."

|

| A Chinese Calligraphy piece of the character for heart/mind - Xīn (心). |

The importance of being able to manifest and render the human heart in society seemed to be considered the most noble of practices in ancient China - to the point that artistry and morality became intimately entwined. Wendan Li illustrates such a situation when he speaks of a master calligrapher of the Tang dynasty,

Liǔ Gōngquán 柳公权 (778–865), p135:

"he was a devout Buddhist. His Buddhist practice surely influenced his philosophy of both life and calligraphy, particularly his emphasis on the necessity of forming a strong moral character as a basis for artistic creation. Once, when asked by Emperor Muzong of the Tang how to write upright characters, Liu responded that it depends on the mind of the writer. When a person sets the purpose of his life upright, he will be able to write upright characters. Since then, Liu’s saying “An upright mind for an upright brush” (心正笔正 xīn-zhèng-bıˇ-zhèng) has been central to the Chinese emphasis on forming a strong moral character as the basis for artistic creation."

Here is a video of myself painting the Chinese character

Xīn (

心) in the ancient cursive zhāngcǎo (章草) script:

|

A comparison of Xīn (心) written by the author (left, from the above video) with his teacher's, Paul Wang (right). Chinese ancient cursive zhāngcǎo calligraphy script. |

No comments:

Post a Comment