"In archery we have something like the way of the superior man. When the archer misses the center of the target, he turns round and seeks for the cause of his failure in himself." - Confucius (6th-5th Century BC), The Doctrine of the Mean (Kessinger Publishing, 2004), p5.

"In Japan the bow has not been used as a weapon for centuries—not even for hunting. Instead, it was discovered that it was an excellent way for people to search for the truth inside themselves. This leads them to a better understanding not only of themselves but of others as well. And that is the first step to universal peace and friendship." - 9th Dan Kyudo Master Onuma Hideharu Sensei, Kyudo: The Essence and Practice of Japanese Archery (1993), p147.

"Archery is a meditative art that requires enormous concentration and control. Like many other art forms that require similar control, breathing becomes the focus of the heart and mind to maintain the calm necessary for absolute precision." - National Head Coach of the US Olympic Archery Training Program KiSik Lee, Total Archery: Inside the Archer (2009), p203.

Today, the first day of the first month of 2013, I practiced archery again for the first time in around 5 months due to the club moving premises. Feeling a little rusty, I began playing around with my technique in order to to improve my skill. The most enjoyable feeling was to rhythmically release arrows in a relaxed yet focused manner. It was very interesting to note the thoughts which arose as each arrow arrived at it's location. Trying to a keep a non-judgemental mind during such an activity is so difficult when success or failure can be defined in such clear terms.

I enjoy watching the Chinese doing archery since it had such a profound role in Chinese society - going all the way back to Confucius, who was an archery teacher. In this post two resources on East Asian archery are going to be compared - one rooted in older tradition; Japanese Kyudo, and the other rooted in more modern methodology; Korean Olympic archery.

The Japanese 'Way of the Bow', known as Kyudo, has a long-lasting relationship with 'dignified' mindfulness practice. As Dan and Jackie DeProspero write in Kyudo: The Essence and Practice of Japanese Archery (1993), p6-8:

"The combination of grace, dignity, and tranquility gives kyudo a solemn, religious-like quality, but kyudo is not a religion. It has, however, been influenced to a great extent by two major schools of Eastern philosophy: Shinto, the indigenous faith of Japan, and Zen, a sect of Buddhism imported from China. [...] Almost every visible aspect of modern kyudo—the ceremony, the manner of dress, and the respect shown for the bow, arrows, and shooting place—has been adapted from ancient Shinto thought and practice.[...] It is Zen, though, that exerts the strongest philosophical influence on modern kyudo. Sayings like "One shot, one life" and "Shooting should be like flowing water" reveal the close relationship between the teachings of Zen and the practice of kyudo. Most of Zen's influence is relatively modern, however, dating back to about the seventeenth or eighteenth century, when Japan as a whole was at peace and the practice of kyudo took on a definite philosophical leaning. It was during this time that the concept of bushido, the Way of the Warrior, reached maturity. And it is generally thought that the word kyudo (the Way of the Bow) was first used in place of the word kyujutsu (the technique of the bow) during the same period. But the original relationship between kyudo and Zen did not begin here. During the Ka-makura period (1185-1333), the samurai adopted Zen as their preferred method of moral training. Zen's lack of hard doctrine, coupled with its ascetic tendencies and emphasis on intuitive thinking, made it the perfect discipline for the Japanese

warrior. It provided the samurai with the mental and moral support necessary to perform his duties, without passing judgment on him or his profession. Kyudo has changed dramatically since the days of the samurai, but the same aspects of Zen that once prepared the warrior archer for battle now enable modern practitioners of kyudo to better understand themselves and the world around them."

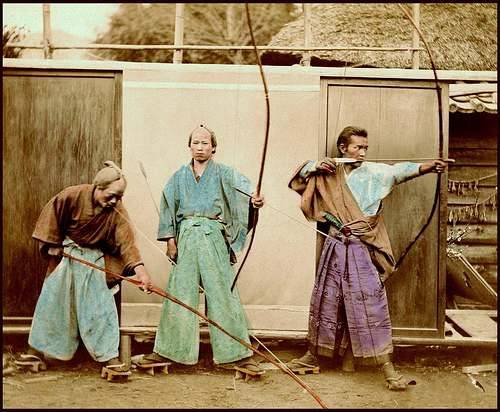

|

| Samurai Archers of the Edo era, Japan. |

"Kyudo is something that you can practice your entire life. It helps improve your posture, circulation, and muscle tone. Also, you forget that mental health is equally important. Kyudo helps us develop and maintain an alert state of mind. In Japan, there are many people in their seventies or eighties who regularly practice kyudo. There is even a man of one hundred and one who still practices."An illustration of the whole-body focus required for the practice of high-level archery is provided by National Head Coach of the US Olympic Archery Training Program KiSik Lee, in his book Total Archery: Inside the Archer (2009), p25:

"In addition to flattening the spine, tucking the hips down and forward tightens the muscles of the abdomen, focusing the holding strength of the body deep within the core, just below the waist line. The position of the core is extremely critical to shooting, as it is the main source of power, calm, and control. An archer should look to this center of power when he needs to stabilize not only his body, but his mind as well."Later, in the same book, Lee again emphasizes the importance of the core and mindfulness of the whole body, p224:

"When one loses body control it is because his source of intensity is no longer contained within the core and is spreading throughout his body in all directions. Maintaining body control is the state of being mindful that all parts of the body must be connected as one. The strength to hold the powerful force of the bow comes from within the core of the body, not in the extremities with which one holds onto the string or the grip of the bow."

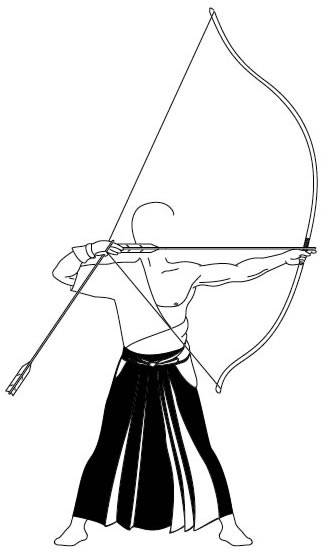

|

| Oh Jin-hyek from South Korea, who won a gold medal in the men's individual archery at the London 2012 Olympics. |

"Kyudo is sometimes called "standing Zen." I think this means that, like Zen, it is very simple, but you must actively practice it to get anything of value from it. It is like writing the number "1" [a single horizontal stroke] in Japanese calligraphy; anyone can do it but to make a really vibrant and strong character takes a lifetime of practice. Kyudo is the same. Everything you are, or think you are, is reflected in your shooting. Therefore, you must have high ideals and pure thoughts. If you think about competing with others or try to impress those watching you, you will spoil your shooting. You must try to learn proper technique so that you can practice correctly. And after that you must spend your life trying to make your shooting pure. That, of course, is difficult because we are human and humans have so many faults. But ...we try."Coach Lee also emphasizes the need for prolonged repetition in order to become a great archer; so that all the various motions and states fit together into a fluid, seamless whole, p242-3:

"Fluidity is a concept all great archers demonstrably possess. ...all great archers, no matter if they shoot the techniques described in this book or not, shoot with an ease that is born of hundreds of thousands of repetitions. Top Korean archers tell of having developed their fluidity by shooting almost 1000 arrows a day, for years during grade school. When the masterful athlete demonstrates profound fluidity in front of a crowd, the sound of applause follows. The applause comes from a deep-seated human understanding about fluidity of motion, an understanding that is greater than ability in even the most practiced athletes, from a crowd who cannot replicate what they have just seen. [...] It is possible to quickly learn one element of a professional athlete’s repertoire, but to incorporate all of the difficult steps into one motion takes fluidity and control. This concept of fluidity, or one motion, does not mean that changes of direction, power, speed, or intensity do not occur, but instead means fluidity encompasses all of the motions and preserves their concepts, rounding the edges so each step blends seamlessly into the one after it."

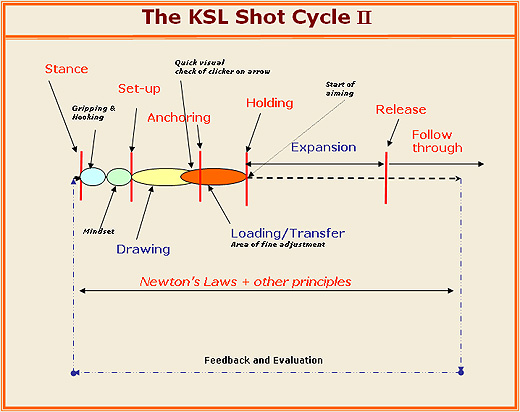

|

| US archery coach KiSik Lee's 'Shot Cycle' methodology for training archers. |

"In its simplest form, archery is a task of conquering demons. Indeed, in all sports, and, for that matter, any passion, one must learn the art of controlling the swells of the heart to achieve virtuoso status. In archery in particular, its repetition and protraction makes the continual battle the athlete must fight with his heart unlike that of any other sport. When an archer stands waiting to begin his gold medal match, he merely walks to the line when the buzzer sounds. Adrenaline only make his hands shake more, and thus he avoids any thoughts that would take him down such a path. Excitement is his enemy. In the moment where he experiences the great fight or flight instinct, he must do neither. He must stand in place, gently and carefully draw back his bow, and launch an arrow into the winds. Moreover, in a twelve arrow match, each arrow means something different. It is true that the first arrows score the same as the last, but as possible chances of pulling ahead of his opponent dwindle, or the closer he gets to shooting the arrow that sets a world record, the more the archer’s heart swells. The more his heart cares. When the desired intangible comes into view, the last arrow to win the match feels immeasurably harder than the first few easy tens. [...] The moment the archer shoots from a place of need, "I need to make a good shot on this last arrow to win,” he has spelled doom for himself. Is it not true that he needed the first arrows just as much? The simple truth is that great strength resides in the act of shooting. The archer who shoots to make his physical expression beautiful is very different from the archer who shoots to hit the center of the target. Ultimately, there is greater happiness to be found in shooting for the beauty of expression than for the sake of hitting a mark. Modern psychology talks about the differences between process-based and outcome-based thought. Process-based thought focuses on the actions that will produce a result. Outcome based thought focuses on the result, using excitement and desire to create performance. While all claims about either method are subjective, some logic exists that would argue outcome based thought creates unrealistic expectations and no path towards them. The archer focused on the process is the one who shoots for beauty. He focuses on the details of his motions, smoothing and blending them together until it is not possible to tell where his arms end or the bow begins. The other archer—the outcome archer—pulls the bow back to his face, shaking with the effort and the anxiety of achieving perfection. The bow is not part of him. It is just an instrument that sometimes does his bidding. He is the archer who is neither rooted into the ground, nor walks freely in the heavens above. He hangs between, forever dreading the snap of the bowstring that will tear him in two."

In order to face the demons of the mind without fear, many archers practice forms of mindfulness meditation. DeProspero writes of this in Kyudo, p29:

"Many kyudojo start the day's practice with a few minutes of meditation. The reason is twofold: First, it allows all the members of the kyudojo to purge their minds of mundane thoughts and calm themselves before practice. Second, it is the perfect way to bring together in harmony individuals of varied professions and personalities. It is from this quiet beginning that we learn to blend harmoniously with our surroundings even as we progress from the relative simplicity of daily practice to the complexities of life outside the kyudojo."Coach Lee confirms the use of meditation in Olympic archery training also, p202:

"Many archers use a variety of breathing/relaxation training to supplement their shooting. Examples include guided meditation, yoga, and focused controlled breathing. With plenty of practice an archer is able to achieve similar relaxation while shooting as he achieves in his yoga classes."DeProspero describes the outcome of such relaxation techniques when manifested in Kyudo thus, p21:

"In kyudo one should be like a deep-flowing river, calm and steady on the surface but with tremendous power hidden in the depths, and not like a small stream, which, because of its noise and turbulence, seems powerful but is really weak in comparison. To further illustrate this point, kyudo masters often cite the following proverb: "A mighty dragon cannot live in shallow water." The analogy is simple: Experience and depth of character are the source of a strong spirit."

Although easy to digest and visualise, the above state of existence is famously challenging to achieve. In Japanese arts this mindset is often referred to as mushin. DeProspero writes of the limited capacity to fully grasp and embody this mushin in Kyudo, p22:

"true creativity is sister to the spirit, and both are born of simplicity. Neither can be learned, like some school subject, nor can they be feigned. They are not a product of the intellect, but flower only when the analytical mind is quieted and the intuitive thought process takes over. Most people believe that the teaching is kept simple and the ceremony strictly controlled to ensure that the techniques are transmitted correctly from generation to generation. That is partly true, but a deeper reason exists: Limiting the student to a certain pattern of movement forces him or her to discard all extraneous action and thought and move into a state of consciousness known as mushin (no mind). For most of us, the concept of mushin seems foreign because we associate "no mind" with no thought—the equivalent of unconsciousness or even death. But mushin is not the elimination of thought, it is the elimination of the remnants of thought: that which remains when thought is divorced from action. In mushin, thought and action occur simultaneously. Nothing comes between the thought and the action, and nothing is left over. When explained in simple, straightforward terms, mushin does not seem particularly difficult to understand. Still, people who have actually experienced mushin— through the practice of Zen or the martial arts— caution against intellectual acceptance of mushin without firsthand experience. They compare it to a man describing what it's like to give birth. He may be able to sympathize with the pain and appreciate the wonder of it all, but because he lacks the experience of giving birth, he can never truly understand it in the same sense that a woman does. That is why a master kyudo instructor keeps his explanations to a minimum and encourages his students to find the answers for themselves. He knows that overteaching only further stimulates the intellect and inhibits intuition, thus denying the student the chance to experience the hidden, inner workings of the art."

This kind of learning through pure physical practice is also described by Lee as essential to deep cultivation of the art of archery, p6:

"a pupil...[should] transcend his technique and truly absorb himself in the brief moment of release. To become an Olympic Champion, this is what is required—total immersion of technique such that the motions become more than a means to an end, and become an end themselves."DeProspero also encourages the archer to aim with spirit - beyond the eyes, p81:

"Although there are several methods of visually sighting the target, most teachers advise their students to aim with their spirit, or to see the target with the "eyes of the mind."The spirit should not be degraded by negative thoughts or emotions, however, as Deprospero states, p4:

"When negative thoughts or actions enter into kyudo, the mind becomes clouded and the shooting is spoiled, making it impossible to separate fact from falsehood. Anger, for example, creates excessive tension in the body which makes for a forced release"Olympic Coach Lee says the only solution to this situation lies in direct, focused action, p253:

"...when the archer stands facing his target, there are no respites from contemplation. Despite feelings of dread, a lack of comfort, and a fear of both success and failure, the only thing the archer can do is shoot his arrow. And in so doing, he must shoot his arrow as he has practiced it a thousand times: unthinking, strong and confident, a true expression of his heart."Kyudo practitioners apparently take this approach even further than the sportsmen, in not even succumbing to positive feelings when shooting. Here is DeProspero, p8-9:

"It is easy to understand the importance of not giving in to failure, but the idea of never allowing oneself to stop and savor success might seem foreign to some. It is this last concept, however, that separates kyudo from other forms of archery, where perfection is usually measured in terms of technical proficiency. A basic tenet of kyudo is that any shot, even one that is seemingly perfect, can be improved. Not on a technical level, because technical skill is limited—the body, no matter how well trained, will age, and physical ability will deteriorate accordingly. But the mind, or to be more precise, the spirit, has unlimited potential for improvement. The key to developing this potential is to understand that the practice of kyudo is endless; the reward comes not from the attainment of perfection, but from its unending pursuit."When I practice archery, I try to take all of the above into account, and I find it such a deeply engaging activity. Here is a short video of me practicing today:

At times I feel that the sight attached to my bow is 'cheating' to a degree. I really hope to get a chance to try Kyudo at some time in my life, and go more with my instinct. Onuma Hideharu Sensei said the following regarding Western bows with sights, p149:

"Western bows are designed for accuracy. If you miss the mark it is possible to adjust the sight or different parts of the bow to improve your shooting. But kyudo is different. If we miss the mark in kyudo we must make adjustments in ourselves—our mind and body."It seems that simplifying archery by stripping it down to it's very basics, in the way Kyudo does, allows one to more easily see one's true self in the practice. DeProspero writes of the great heights of Kyudo skill and spirit thus, p3:

"In... the highest level.. the target is neither goal nor opponent; instead, it is seen as an honest reflection of the self. Rather than focus on the target, the... archer concentrates on the quality of his thoughts and actions, knowing that if they can be made pure and calm, his body will naturally correct itself and the shooting will be true. To achieve this the archer must unify the three spheres of activity—mind (attitude), body (movement), and bow (technique)—which form the basis of shooting. When these three elements are unified, rational thinking gives way to feeling and intuition, the thoughts are quieted, and technique merges with the blood and the breath, becoming spontaneous and instinctive. The archer's body remains completely relaxed, yet is never slack. Always alert, his spirit pours forth, channeled into and beyond the ends of his bow and arrows until they become like natural extensions of his body. In this state it can be said that the arrow exists in the target prior to the release; there is no distance between man and target, man and man, and man and universe—all are in perfect harmony. This is true, rightminded shooting."

Great article. Very thought-provoking... I've often thought of Archery as how I best practice meditation (though I meditate in other ways too), but still great to hear the thoughts of the masters...

ReplyDeletecool! archery is more than just a sport!

ReplyDelete#Awesomearchery

I would like to say that this blog really convinced me to do it! Thanks, very good post. youth bows reviews

ReplyDeleteSure, The art of archery can also be a rigourous physical discipline which tones the body. Thank for sharing with me!

ReplyDeleteadventurefootstep.com